Yes. The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in December 1865, formally abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime, marking a pivotal moment in U.S. history by ending the institution after the Civil War, building upon the Emancipation Proclamation to legally free millions and laying groundwork for Reconstruction.

Article XIII. Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments, followed by the 14th (citizenship and equal protection) and 15th (voting rights).

Except as punishment for a crime

This clause remains controversial, as it allows for forced labor within the prison system, a practice many critics view as a continuation of forced servitude. Criticism of forced labor prison camps through different times and places in recent history is shown differently from what people everywhere are told about what it means to be an American. (As seen on TV)

The population in our prison system has continued to be disproportionately racially biased. Most people in prisons in the United States could completely recover with the right psychiatric care. Psychiatric care in the United States, however, is almost not ever in place for this purpose. Often it is even in place for a default purpose of keeping a steady supply of slaves for the prison economy, an interim holding area following the living hell of public schools, there to tell Americans lies about our own country during our earliest phases of brain developmental failures.

Critiques of the Soviet Union, of course, no longer apply. Don't be so different, it is foolish on behalf of all of us.

That's so Bohemian

The Kingdom of Bohemia was an Imperial State in the Holy Roman Empire. As it stopped being an unavoidable part of the experience of the average human being to know that ghosts are real, more and more of the world anyone could have ever wanted was built like a house of cards on top of massive amounts of work done by slaves. In the Czech language a word that sounds like "robota" was the term for the forced labor prisons. Slavery in very Slavic areas was most understandably not exactly congruent to racial differences as much as an individual's failure to act Christian. As our world became more and more paved over and mechanized, it unfortunately naturally become less obvious that God is real and Christ lives among us as the Word of Truth and Love. If not on TV, exactly as seen on the magic shampoo bottle and everything nice. The dream of the continuing industrial revolution, as we more and more rapidly approach it, is for machinery to take care of everyone and free all of the human beings up to be the organic component of the spaceships. Little green men who live happily in the sunshine focused on their hobbies and happiness all day and eat only dirt and water and the occasional bug, and defend far-future galactic special interests with psychic mind powers. ROBOTS, BRO.

In the spirit of the reason of the season, even out of which, in a timeless fashion meant for humans, maybe we could all come together for peace and education, as seen in the ideological framework of some television shows. Especially meant to discourage biting our friends. Believe me when I say that I do understand how shockingly difficult it can be, as a human being, not to deny my own emotions, perhaps, but literally to survive a mostly average human existence - it starts to seem more and more extremely unlikely that God does not exist. Try to explain this in some other way without ignoring most of the evidence all around us...

WARNING There are most likely VERY GOOD REASONS that mammals CANNOT BE GREEN WARNING

Do your best not to commit any crimes, make good choices, do your best to be a part of the society built on top of the glass ceiling. Reach for the stars, so that if you fall you land in the clouds. Ask someone who knows! I don't. Don't bite the hook of your own misery, regardless of what other people are doing, even to you in cruelty. Your emotions are only there to lead you into making bad choices for yourself and others.

The Internet is an incredible resource for learning new skills, as never before so easily found at any time in history - much of which has already been deleted by gigantic winners.

Some things are just that hard to learn to do! Saving the human race? Nothing that's really worth doing is possible! Global collaboration is currently strongly proving it is even worth trying to save ourselves. There are many obvious examples all around us, as you can see for yourselves that I needn't list these extremely good reasons for humanity to exist here! We see them all around us and we will be more than ready to tell a possible near-future evil AI overlord why humanity is worth our own existence. There's no reason that I should expound on the matter and list these excellent reasons to counter a misanthropic viewpoint that humanity is worthless garbage. We can all see these for ourselves everywhere we look at the world around us. At the end of the course there will be an open pop quiz to list reasons for us to explain to the evil AI from the future to save humanity ourselves like rats from a sinking ship.

This should sound familiar from your previous course material. A lot of people know about the idea of sharpening a pencil, but surprisingly few people are immediately aware of the purposes for a pencil beyond stabbing other retards. While this class does not directly cover the topic, this area has been set aside for you to scream or weep in futile agony into the void:

As Cioran said to Plato, we would never think to be scared of the dark if not for the occasional bit of light in it.

Required course materials are essential items (textbooks, software, lab kits, supplies) needed for successful completion of a class, detailed in the syllabus and found via the school's bookstore or online portal, with digital options often available, but instructors provide specifics for what's truly necessary to meet learning objectives.

Required: Mandatory for assignments, lectures, and objectives (e.g., specific textbook, software, goggles).

Recommended: Strongly advised extras for deeper understanding (e.g., supplementary guides, practice sets).

Suggested: Optional items that might help but aren't essential.

Course Syllabus: The primary source, often listing required items in a "Start Here" module or announcements.

School Bookstore/Portal: Your university's official source for purchasing required books and supplies.

Learning Management System (LMS): Check Canvas, Brightspace, or other platforms for digital links or modules.

Textbooks (physical or e-books)

Software, online access codes

Lab equipment (goggles, kits)

Calculators, notebooks, pens

Headsets

Always check the syllabus first for specific instructions, as materials vary widely and can include more than just books, impacting your success in the course

A C compiler is a specialized software tool that translates human-readable C source code into machine code that a computer's processor can execute.

For professional development or large projects, these local compilers are industry standards:

Online compilers allow you to write and run code directly in your browser. These are ideal for beginners or for testing small snippets.

| Platform | Key Features |

| OnlineGDB | Includes a powerful visual debugger for stepping through code. |

| PlayCode | Uses WebAssembly for 100% browser-based execution, allowing for offline use. |

| Replit | Supports collaborative real-time coding and cloud hosting for projects. |

| Programiz | A simple, fast interface specifically designed for learners. |

| Compiler Explorer | Advanced tool for inspecting how different compilers translate C code into assembly. |

When you "run" a C program, the compiler performs four main steps:

As in many classes, our first program will be a simple program that outputs: Hello world

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("Hello world\n");

return 0;

}

Almost all C programming environments include the "Standard Input/Output Library." We start by including the header for it with a preprocessor directive:

#include <stdio.h>

The printf() function is usually there to "print" a formatted line of output. On modern computers the output is usually to a screen, not a printer.

No, and it is not necessarily part of the C language. At some point in the past it did or did not start to work this way. Many computer operating systems have special functions that are system calls to the operating system. The printf() function can do more than just output Hello world and makes formatting variables very convenient. However, a more direct way to output Hello world on many systems would be to directly call the write system call.

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

write(1, "Hello world\n", 12);

return 0;

}

The operating system starts running our program by calling the main() function. We almost always define a main function of a program as the entry point for the operating system to start running the program.

The first thing we do is call the write system call as a function in our program. It takes 3 parameters. The first is an integer, 1. In this case the number 1 refers to the number of the "file descriptor" for writing the data. This is also called "Standard Output." The second parameter is the data we want to output. In C we define text data in quotation marks. Our text data is "Hello world\n" which has a \n at the end. That shows a new line, as if we had pressed the Enter or Return key. The third parameter is the size of the data, 12. If you count all of the (bytes of) characters and data, you will see there are 12 bytes. H, e, l, l, o, space, w, o, r, l, d, and a new line at the end.

Now we return from our main() function. In many operating systems the program returns an integer return code. The number 0 usually means success. Different integer return codes are often specified for different error number codes. Functions are declared in their prototype. The main() function is often defined as a prototype: int main(int argc, char **argv). Argc is the number of parameters when we run the program, argv is the character bytes of each parameter, and the function returns an integer return code.

Many sytems already come with an echo program by default. The echo program usually just outputs its own parameters one by one with not many frills. For example, echo Hello world would output Hello world.

The echo program loops over argv for argc times. The first parameter is Hello and it outputs that, then the second parameter is world, which it also outputs, then it is done. Usually it also outputs a new line by default for us.

In many operating systems file descriptors are numbered channels open for input and/or output. The file descriptor numbered 0 is usually "Standard Input," we usually read input into the program there. File descriptor 1 is "Standard Output" where data is written out. Usually file descriptor 2 is also specified as "Standard Error." Output written to fd 2, "Standard Error" is similar to "Standard Output" but has a difference when programs are put together in pipelines. A pipeline puts the output from a program into the input of the next program. It sends on the output on fd 1, but not the errors on fd 2.

Many operating systems also commonly come with a cat program by default. With no parameters, cat just copies its input to its output. If someone started running cat and typed Hello world into it, it would just output it right back to the person. In a pipeline, a program's output can be sent to another program. So, echo Hello world | cat would use the echo program to output Hello world and send it to the cat program, which in this case would just output its same input, Hello world.

You need to leave now. Get out of here.

I am VERY serious. People start acting like someone needs to explain that murder is wrong. I... I can't tell if people are asking me if murder is wrong, am I supposed to know? It turns out that I do know. Murder is wrong. If I were expecting anything of everyone it was that people do know at least that murder and stuff like that is wrong from former experience. I am absolutely standing by this opinion, everyone does know that murder is wrong. I can't believe this many people are still asking me if murder is wrong. It is absolutely wrong. People are expected to know this. Not all of the students feel the same way as you. You are expected to be able to deal with this yourself somehow.

A computer really is pretty much based on a calculator. A CPU does one instruction at a time. 1 + 1. Store answer. It stores the answer at a memory address somewhere in the computer. It can store many, many numbers. It can load a number from a memory address and add 1 to it. A computer does a pretty much unimaginable number of things like this every second. Program machine code is a list of instructions that a CPU goes through one by one. There are also instructions to compare a result at a memory address and do different things based on the result. As a 0 might mean success, so the code does one thing, and a different number means there was a specific error. There are also instructions to jump to other parts of the machine code. More and more system code is built up from this. The C programming language is a good middle-level language between the machine itself and a computer programmer. It was designed to be "just enough." An important goal of the language is that it is not machine code. With enough of a system in class, the same program in the language can be compiled to many different types of computers.

A function is a grouped context of a list of instructions. When a function is called, it is "pushed onto the stack," and the instructions listed in the function code are done one by one by the CPU. It goes through the list of instructions and does each thing, including some comparing to make decisions and jumping around through the code. When the CPU reaches the end of the function it returns and "pops off the stack" back to the context which called the function. A function can also return data upon completion to the context which called it.

C has specific types of data. There are simple named types included such as int for an integer number, float for a floating point number which is a real number with a decimal place, char for a character letter, number, or symbol which would show up on a screen. These types are limited by the space it takes to store them. A char is usually one byte, eight bits of data. Each bit of data can be on or off, 0 or 1, true or false. In binary digital electronic computers everything is based on complicated networks of transistors being used as switches which can be on or off.

Base 10 counting is what we're used to. 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and now we have run out of digits to show the numbers and we go back to 0 but now we have one 10. Then we start adding numbers from 10. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, and now we have 2 units of 10 - 20.

Binary is base 2 counting. 0, 1, and now we have already run out of digits to show the units instead of continuing with more types of digits, and we go on, not to the 10's, but the 2's. 0, 1, 10. Then we keep going. 0, 1, 10, 11... and now we are not to 100, 10 times 10, but to 4, 2 times 2: 100. The C language usually has a way to write these binary numbers. 0b0, 0b1, 0b10, 0b11, 0b100, 0b101, 0b110... 0b111 is the number 7.

I understand what you're saying, and I know the risks. I just really do feel this strongly that all of our students should be highly trained and adept at both pencil safety and correct usage. "Computer science is as much about computers as astronomy is about telescopes." - Edsger Dijkstra

Ask the math teacher.

Functions get pushed onto the stack and the computer runs through each statement of code. Each statement has to be valid in the C programming language, or the compiler won't be able to compile it correctly. This is no guarantee that it will run correctly. It can take experience to be able to write code that compiles and runs as intended. In my compiler in the year of our Lord Jesus Christ 2026, write is no longer there. My compiler now gives me an error that it can't find the write function, even though on this OS it is a system call. My compiler gives an error that this is an "implicit declaration" of this function, it cannot find the function anywhere. The system call is no longer implied by default to be a function. Right now and in the forseeable future, I have to use the preprocessor to include a header for some slop.

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

write(1, "Hello world\n", 12);

return 0;

}

This is very unfortunate! It is not supposed to work this way. It does compile correctly now on my system. We have no idea how this works anymore. It has gotten too complicated for any human being to understand. Robots are laughing at us, but they are not teleporting back in time to kill Sarah Connor yet. We need to act quickly. Luckily, modern computers are able to run many billions of instructions every second. We have plenty of time.

#include <unistd.h>

This is a preprocessor directive. It includes a header file which defines the write function, which upsets us greatly. We are only human.

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

This is the definition of our main function. Remember, our OS enters the program here to start running our non-AI slop.

write(1, "Hello world\n", 12);

This is our call to the write() function. You may remember this, although possibly very differently than the well-known character from The Simpsons, Troy McClure.

return 0;

This statement returns the number 0 from the program.

}

Syntax. The compiler needs this. This is the end of this main function, our group of valid C statements.

Here is another example of a simple program. This is a simple implementation of the echo program described above. This example is meant for simplicity.

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int argi, length;

for (argi = 1; argi < argc; argi++) {

for (length = 0; argv[argi][length] != '\0'; length++);

write(1, argv[argi], length);

write(1, " ", 1);

}

write(1, "\n", 1);

return 0;

}

In this example, I have introduced variables, I have started to introduce the concept of arrays, and I have introduced a new type of statement for looping.

int argi, length;

These variables are integers. The types of variables are different. An integer in C can only store up to a certain magnitude of integer, and then something can go wrong. These are numbers like 0, 1, 2, 3... and also -1, -2, -3... it stores up to very large numbers, but not that large. If you need to store any integer including ultra-neptunian-gazillions and anything, you need to figure out a way to do it or a library someone already made.

for (argi = 1; argi < argc; argi++) {

This is a for loop. It is not a function, this is syntax in the language. Some of these things are keywords in the language, int, for. Keywords are used for stuff and cannot be used for code stuff you name yourself. You name the functions and variables, though the OS usually treats the main function as a special entry point for the program. A for loop has an initializer, a condition, and a step.

for (initializer; condition; step) {

Our loop initializes the integer which we have named argi to 1. We are going to loop over the argc parameters in the array argv (of arrays of chars) of our program. For arrays we usually start at the index of 0, but in this case, argv[0] (at index 0) is an array of chars which is the program name. We want to skip that for our program, so we start at 1. Our condition is that argi is less than argc. On each step we add 1 to argi. When argi is no longer less than argc (equal to it) we exit our loop.

for (length = 0; argv[argi][length] != '\0'; length++);

This for loop measures the length of the character byte array at argv[argi]. Usually we have a block of code between { and } brackets, but we don't necessarily need this. If a block of code is only one statement, we can often leave these out. In this case the block of code is no statements whatsoever, so we just have a ; after the loop declaration. This loop does nothing except count the number of character bytes in argv[argi] and store it in the variable length.

First we initialize length to 0. In the C language, valid character "string" arrays are "null-terminated," they are an array of the byte values of the characters, and at the end they must have a byte value 0. We often write that byte value explicitely in the C language as '\0'. Many of these things are equivalent ways to write the same thing, but more clear depending on the context. In C we can write 0 for the number 0, or 0b0 to more clearly write the binary representation of the number 0, or '\0' to show a character "null-terminator" byte with a value of the number 0 which shows the end of a valid C language character byte string. This loop keeps incrementing our lengthargv[argi][length] does equal the null-terminator byte, and then we exit this loop. Our length variable not shows the number of character bytes.

write(1, argv[argi], length);

write(1, " ", 1);

We needed this for our write call. We write "length" bytes from "argv[argi]" to "file descriptor 1" and then we also write a space after that between this and our next one.

write(1, "\n", 1);

At the very end we make sure to output a new line. Finally we return a 0 to indicate success.

We can use the cat program to output our source code file, our cc command means the C compiler, and then we can run our version of the echo program to say Hello world.

~ $ cat echo.c

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int argi, length;

for (argi = 1; argi < argc; argi++) {

for (length = 0; argv[argi][length] != '\0'; length++);

write(1, argv[argi], length);

write(1, " ", 1);

}

write(1, "\n", 1);

return 0;

}

~ $ cc -o echo echo.c

~ $ ./echo Hello world

Hello world

~ $

The cat program hopes that all of its parameters are filenames (in this case, echo.c) and loops over them, opening the file, reading it, and writing it to file descriptor 1.

The cc program compiles C language source code. In this case our whole program source code is in one file called echo.c so we tell the compiler -o echo which means output this compiled source code to a program file called echo.

We don't type echo to run our own personal version of the echo command, we type ./echo. Typing this means that in the current directory we are in, "./" we find our own program file echo to run that instead of any system-wide version of the echo program.

Our stupid program compiled and ran fine, but it did something we didn't quite want, or didn't expect. Upon careful examination of the system echo command and our own code to do this, there is a difference if we look closely. This program is supposed to write back all of its parameters. Our version does something else, though. Our version prints a space at the end of the line, which we did not intend. It can sometimes take a lot of time and effort to get our programs to do exactly what we want. This is a bit more complicated, and now we have reasons to do a few new things in our source code. One of the main things I am going to introduce now is the concept of comments. In source code, these are meant only for human beings. The source code is not the machine code, and comments allow us to leave notes and explanations for ourselves. A way to put a comment in a C source code file is to put things between a

/* and a */

The comments here are meant to explain the changes we have made to decide what the program does. We also now have a reason to write a custom function writearg which we call twice. It makes sense to put this in its own function instead of typing the same code in more than once. Sometimes there are reasons to do this differently, but in this case it seems like a good enough excuse. We are also using the keyword if for the first time. The code block for the if statement depends on the condition. If argi is still less than argc at the end then it means there is one more parameter left for us to write, but this one does not get followed by a space.

#include <unistd.h>

/* our first custom function: writearg

* takes a character byte array as a parameter and returns nothing (void type)

*/

void writearg(char *arg) {

int length;

/* find length of "arg" character byte string */

for (length = 0; arg[length] != '\0'; length++);

/* write the "length" character bytes of "arg" character byte array to file descriptor 1 */

write(1, arg, length);

/* and return nothing, of type "void" */

return;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int argi, argnl;

/* we have a new variable "argnl" which we set to one less than "argc" */

argnl = argc - 1;

/* we loop as before, but only to one less than before */

for (argi = 1; argi < argnl; argi++) {

/* and now we call our custom function "writearg" to write each string */

writearg(argv[argi]);

/* and we do write a space, but not for the last one. we exit at "argnl" now */

write(1, " ", 1);

}

/* and is there one more left? */

if (argi < argc) {

/* if so, we call writearg one more time for the last one. but no space! */

writearg(argv[argi]);

}

/* and finally we write our new line at the end */

write(1, "\n", 1);

/* and return 0 for success as we exit our stupid program */

return 0;

}

I'm trying to help you learn this stuff! I genuinely think it would be helpful to anyone! I'm trying to be your weird friend!!!

length = 0;

One equal sign is for assignment. The variable length is on the left-hand side of being assigned to the value 0 on the right-hand side.

if (length == 0) {

A double equal sign is different, this is comparison. We are evaluating whether the variable length is equal to 0 as the condition of an if statement.

We can add one to length

length = length + 1;

Or we can do the same thing with the increment operator, ++.

length++;

Some people think this is a joke. I don't really understand the joke.

We can do other types of comparisons. What if length is less than or equal to 0?

if (length <= 0) {

There are a bunch of different types of variables - int, float, char. There are more than a few different operators that work in different ways to do different things, flow control keywords such as for, if, and return, and other things that do stuff. It takes some practice to learn it all, but the C programming language is different from many other languages in different types of simplicity. It is usually closer to how the computer machinery works, and the entire language has less stuff overall. So, if you learn the entire language, you have learned more about the machinery than in many other languages. Learning the whole language often seems like more of a challenge, but when you are done learning it, you have truly learned the entire language.

The awk program is smarter than me. It's a sort of a weird programming language. In this example I am using the gsub() global substitute function to replace all of the HTML <h3> tags in this document with themselves and also a link to themselves at that line number. I am doing this for easier bookmarking.

awk '{ gsub(/<h3>/, "<h3 id=\"L" NR "\">") gsub(/<\/h3>/, " <a href=\"#L" NR "\">bookmark</a></h3>") }1'

I searched online for how to do this. Many operating systems include the awk command. I should learn to use it better someday. I used this command as a filter in the shell:

awk '{ gsub(/<h3>/, "<h3 id=\"L" NR "\">") gsub(/<\/h3>/, " <a href=\"#L" NR "\">bookmark</a></h3>") }1' < index.original.html > index.html

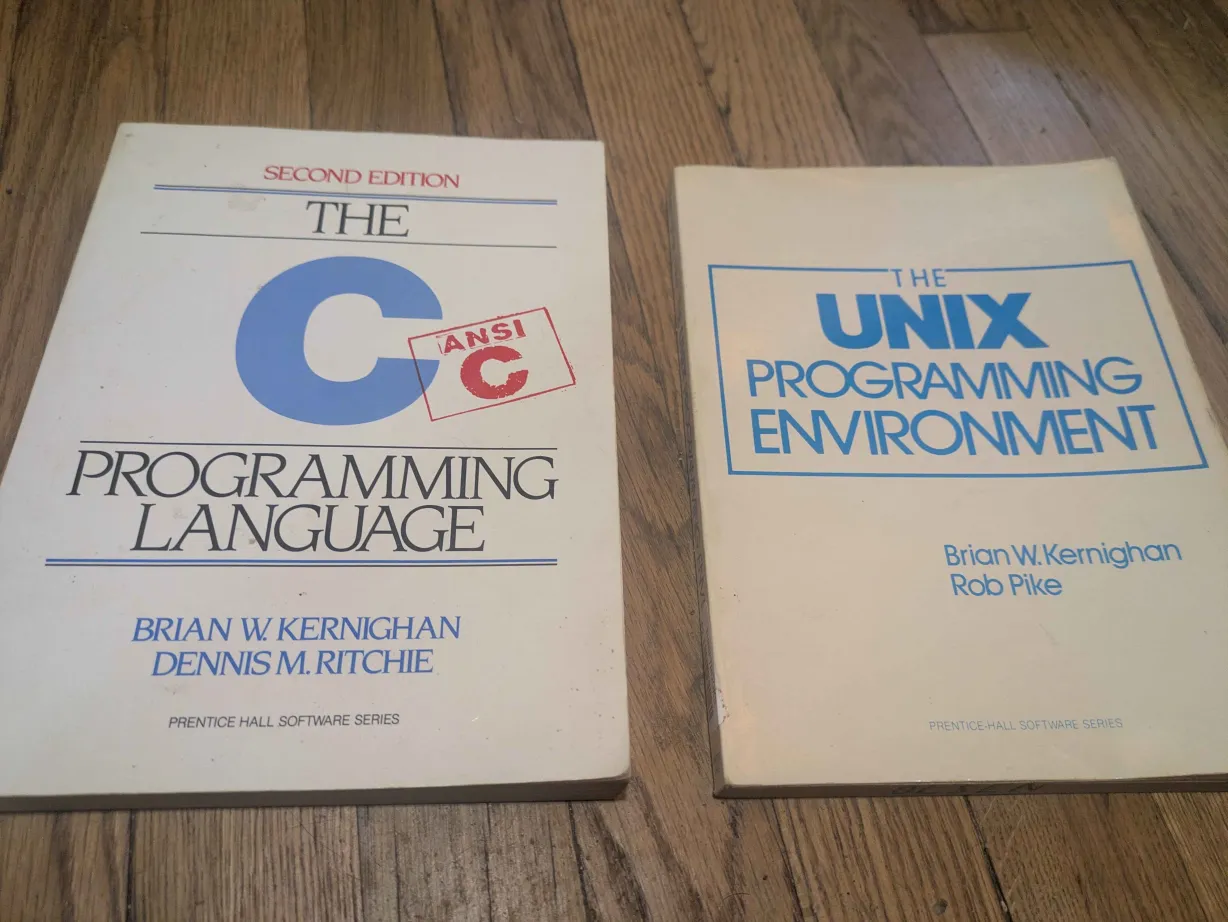

These are the definitive textbooks on the C programming language and on Unix-like operating systems.

This topic is the reason that the C programming language is known to be difficult, and is also the main thing that makes it usefully closer to the machine level. This is the part that is hard to learn, to teach, and to explain. This is a place we can easily make errors. In easily mixed up areas of the computer's memory there be dragons. However, without an understanding of memory management there is no understanding of the C programming language, nor much of an understanding of what a computer is.

Pointers are a different type of variable. We have already seen these, but they have not been explained.

char c; c = 'c';

This type of variable is a char, one character byte. This type of variable takes up one byte of memory space, eight bits. A bit in memory is the most basic storage area in memory, it can either contain a 0 or a 1. A byte is eight bits in a row. It can show 256 different states: 0b00000000 is 0, 0b00000001 is 1, 0b00000010 is 2, 0b00000011 is 3... 0b11111111 is 255. Hexadecimal notation is base 16 which is commonly used and helpful because it maps to binary better than our normal base 10 numbers. 0x00 is 0, 0x01 is 1, 0x02 is 2... 0x0A is 10, 0x0B is 11, 0x0C is 12... 0x10 is 16, 0x11 is 17, 0x12 is 18... 0xFF is 255. The character 'c' has a numeric value of 99. The bit pattern for 99, the letter 'c', is 0b01100011, 0x63. A number with a leading 0 is in octal, base 8. 011 is the number 9 in octal. After 07 the next number is 010, which is 8, then 011. A base N numeral system has N total symbols for digits then wraps around to start counting units of N, then again for units of N*N. We are accustomed to base 10 which counts from 0 to 9, then 10's, then 10 times 10 are 100's, then 1000's... We have stored this value in memory. It is a binary representation in the tiny transistors in the computers used as on/off switches in the computer's memory. To the human programmer or very smart AI (you) it is in the character variable called c.

char c; char *pointer; c = 'c'; pointer = &c;

There is another related type of variable called a character pointer. The size of a pointer depends on the machine type. A pointer describes an address somewhere in the computer's memory. All of the variables are somewhere in the computer's memory. When we begin running a function, it gets pushed onto the stack which has a certain amount of a certain type of memory. Variables are described there, they exist in the stack memory. The stack usually does not have very much memory available compared to the total memory available in the computer. We can request more memory from the heap in another way.

In this example we have char c declared on the stack, then char *pointer declared on the stack to store the memory address of a char variable. We set our c variable to the letter 'c', and then:

pointer = &c;

Here we set our pointer variable to the address of the variable named c.

We have also seen arrays. They can be declared on the stack, at least up to a certain amount of memory. An array is a designated chunk of memory all in a row.

char array[10];

This is an array of 10 character bytes all in a row, declared on the stack. This is one variable that is 10 character bytes.

pointer = array;

We can set the pointer to array, this really means the address in memory where our array starts.

c = array[0];

We can set our c variable to the first character in array, at index 0. We start counting at 0. The index means this many character bytes added as we count through the array from the beginning, so the beginning plus 0 is still the beginning. We start counting at index 0.

pointer = &array[0];

or:

pointer = &array[1];

or:

pointer = &array[9];

We can also set the pointer to the address of the character byte at an index of the array.

pointer = &array[10]; /* error! */

This is an error! Array is a list of 10 character bytes. The index starts at 0, so the end is at index 9. Index 10 is too much, this is one character byte past the end. Our variable pointer is still set to this memory address more or less fine, but it is now in an undefined region of computer memory that is not part of our declared variable array. This is just past the end of it, which is undefined and is likely to cause errors.

pointer = NULL;

It is also worth mentioning that we have a new way of expressing the number 0. A null pointer is a pointer to the address, number 0. This is pretty much always an error if you try to work with the memory at the address 0, but it is a way to express the number 0. This is useful if we want to compare the pointer to a valid pointer. If the pointer is equal to NULL, then we have a good way to know it has not been set to a valid address.

*pointer = 'c';

We call this dereferencing our pointer value. We are setting the value of the variable pointed to by pointer to the letter 'c' here.

pointer[0] = 'c';

This also works as if pointer were an array, however:

pointer[9] = 'c';

This may or may not work correctly. It depends on what is defined in memory 9 character bytes after the address pointed to by our pointer variable.

char c; char *pointer; c = 'c'; pointer = NULL; *pointer = c; /* error! */

This will give an error and not work correctly. Our pointer variable has been set to NULL, the value 0 instead of a valid memory address. Then we try to set our c character byte variable to the value pointed to by pointer. We try to dereference a null pointer which is absolutely an error. We should almost absolutely not ever be working with the memory in the computer at address 0. This is a null pointer error.

The stack only has a certain amount of memory available to us. Even if it's eight megabytes or more, we will eventually have problems of running out of space on the stack. A char variable takes up one byte of space, so although eight megabytes may not sound like a lot of space, this is several millions of character bytes. However, we will eventually run out of space on the stack. The stack is an area of memory meant for context. A function call pushes that code onto the stack, runs through the code to the end of the function, and pops it off the stack again, often returning an answer to the calling function above it. It pushes that context onto the stack, runs through it, and pops it off the stack again back into the context above it. Eight megabytes of space is a common modern amount of total space available to use there, many millions of character bytes worth of space in memory. A CD ROM for example, however, is commonly many hundreds of megabytes of memory storage data. There's no way that can fit on the stack. A modern computer usually has more total memory available than the total space on a CD ROM, but it is on the heap, not the stack.

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

char *allocate_gigabyte() {

char *pointer;

/* one gigabyte of space! */

pointer = malloc(0x40000000);

/* a null pointer means malloc returned a failure */

if (pointer == NULL)

write(2, "memory allocation failed\n", 25);

return pointer;

}

This is also our first example of writing to file descriptor 2, not 1. File decsriptor 2 is for writing error messages.

There is a function called malloc() defined in the <stdlib.h> system header file on my operating system, for the purpose of memory allocation. This is a function to allocate an entire gigabyte of system memory on the heap. We need to keep track of this ourselves now that it has been allocated. It is there in every context in our program now, until we free() the allocated memory. If we lose track of our pointer to the beginning of our gigabyte of space we won't be able to properly free() it to clean up our allocated space in memory. The malloc() function will return NULL for us to indicate an error, like if the computer just doesn't have enough memory for us. If malloc does succeed, our variable pointer now points to the beginning of a character byte array which is the size of an entire gigabyte of character bytes in the computer's memory, all in a row. Any index up to 0x40000000 - 1 now works fine in our allocated array of memory stored on the head. When functions are called this is still in the context, when they return this is still in the context, it is there until we are sure we are done and free() our allocated memory.

/* we need to keep track of this ourselves * and free allocated memory when we are done with it */ free(pointer);

We need to keep track of this ourself. This may seem weird, tedious, and liable to get confusing and cause errors, but this is much closer to how computers do actually work than many other programming languages. This language is meant to not be machine code, though, so on enough of a computer system it will compile to machine code that works on any different system that supports this (still today, more than 50 years later, the most commonly available) programming language. Compared to other languages, understanding pointers and memory management is the only hard part. Other programming languages (Java, etc) have garbage collectors and reference tracking and handle memory allocation for the programmer. Something funny but annoying that happens to C programmers when they program in Java is that the garbage collector free's memory that I am still trying to use. After programming in C for a few years, I noticed I was having a completely opposite problem in Java. The garbage collector was stealing my allocated objects from me when I did not keep track of their references well enough.

char *start, *end; start = allocate_gigabyte(); if (start != NULL) end = start + 0x40000000;

Say we want to use our function to allocate a gigabyte of memory on the heap, then we want to keep track of the start and the end of our allocated array of character bytes in computer memory. We set our start variable to the returned array. It is named and pointed at by the address of the very first character byte at index 0 where the array starts. Then we have another character byte pointer variable called end, and we set that to the start address variable plus the number of one gigabyte's worth amount of character bytes. The end variable really points to one past the index at the end. By the time we get to the end variable, we will know we got to the end of our allocated array of memory space.

char *pointer; for (pointer = start; pointer < end; pointer++) write(1, pointer, 1);

This example very slowly and tediously loops over the entire gigabyte of allocated memory in the array and uses write to output one character byte at a time to file descriptor 1, the standard output of our program. The pointer starts at start and keeps incrementing by 1 byte address while it is less than the memory pointer variable end, until it stops there.

#include <unistd.h>

/* I got a bad feelin' about this

* somethin' ain't right */

void nextletter(char letter) {

letter++;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

/* our character variable */

char c;

/* is set to the character byte 'c' */

c = 'c';

/* and we try to go from 'c' to the next character byte, 'd' */

nextletter(c);

/* write doesn't take character bytes

* it takes the address of an array of character bytes and its length

* the address of one character byte can be used as an array of length 1 */

write(1, &c, 1);

/* by the way, those double quotes are different */

write(1, "\n", 1);

return 0;

}

This program outputs the letter 'c'! We wanted to increment our variable to the next letter 'd', but our nextletter function incremented our copy of the variable pushed onto the stack. When nextletter returned, that variable went out of context. We needed our function to take the address of our variable (or array. a pointer often points to the start of an array.) We will rewrite this so that in the context of nextletter we are incrementing the char c variable defined in the context of our main function, not a copy of it.

#include <unistd.h>

/* ok. much better. we take a character pointer not a character */

void nextletter(char *letter) {

/* and we increment the character byte at the dereferenced pointer address

* this is the true "char c" variable in the main function context above this function call */

(*letter)++;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

char c;

c = 'c';

/* we pass the address now! this will work correctly */

nextletter(&c);

write(1, &c, 1);

/* by the way, those double quotes are different

* the double quotes are different because they define a character string

* a string is a character byte array with a '\0' null byte at the end

* an array variable is defined by a pointer to the start of it

* so we're passing a pointer to an address of the character byte string array "\n" */

write(1, "\n", 1);

return 0;

}

Now our program outputs the character byte for the letter 'd' correctly. The char c variable is incremented in the context of our nextletter function. In that context we are working with a character byte pointer to the address of the char c variable which is defined in the main function. In nextletter we have passed the memory address to that variable, not the variable and a copy of its value.

Yes, the * character is also used for multiplication. There are differences between unary operators in C, binary operators have a left-hand side and right-hand side, and there is one ternary operator.

*pointer = 1;

In this example it is the unary operator to dereference the pointer. The variable pointer contains a memory address, when we dereference it we are going to the actual value stored at the address.

*pointer = 1 * 1;

Now on the right-hand side of the assignment operator "=" we are using it for multiplication. 1 * 1 is one times one. We put the answer into the dereferenced variable at the address in the pointer.

1 * 1 is using the * for multiplication. It is called a binary operator here.

char boolean; boolean = 1; boolean = !boolean;

This is another unary operator. The ! before a value just swaps an evaluation to true or false. The variable boolean evaluates to false in a condition if it is 0 and is just there by itself, and evaluates to true otherwise - as long as it is not part of a comparison. This is usually considered a bit less clear than an explicit comparison such as: if (boolean != 0) {

return (boolean? 0: -1);

This is the only ternary operator. We are returning a 0 or a -1. If the variable boolean evaluates to true (non 0) then after the ? is a 0, we return 0. Otherwise boolean is equal to 0 which evaluates as false, after the : is the -1 which we return in that case. The ternary operator in this case is just shorthand for:

if (boolean) return 0; else return -1;